From the valleys of the West Slope, Colorado rivers are a cornerstone of our communities, economy, environment, and shared way of life. However, our state’s landlocked status means that the rivers’ water isn’t naturally accessible for a lot of Colorado communities; most often, we have to bring the water to us. Snowpack melts from mountain peaks and irrigates through tunnels and pipes to reach communities throughout the state. Water, as a seasonal and limited resource, is increasingly scarce as snowpack peaks earlier and warm temperatures arrive earlier.

Despite the fact that Colorado is home to some of the best water recreation opportunities in the West, we’re facing a prolonged drought — and all the environmental issues associated with it.

Consequently, many Colorado rivers aren’t in great shape. The damaging effects of climate change and lingering impacts of overuse, poor management, and energy development continue to devastate our water supplies.

Summer after summer, our rivers seem to be shrinking. However, something about this summer is remarkably different. Currently, abnormally dry conditions are impacting approximately 4,023,000 Coloradans — about 80% of the state’s population.

Let’s look at a few of the rivers across the state to reflect on the past and what our new normal may look like.

Hold On: How Do We Measure Water?

We use the measurement of cubic feet per second (cfs) to measure water in motion. One cfs represents 7.5 gallons of water flowing by a particular point per second.

Imagine one unit of cfs as roughly the size of a basketball. So when we say a river has 449 cubic feet per second, imagine about 449 basketballs bouncing downstream every second!

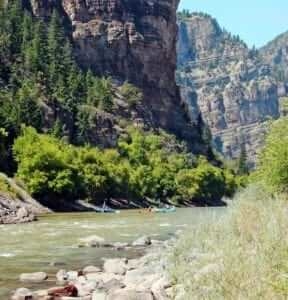

Colorado River

Image Credit: Don Graham.

Glenwood Canyon:

Flows on July 23, 2018: 2190 cfs

Average flows on July 23 over the last 51 years: 4270 cfs

That’s over 2000 cfs less than the past average; that’s roughly 51 percent less than the average.

Also known as the “American Nile,” the Colorado River supplies more water for Coloradans than any other river in the state through pipelines from the West Slope to the Front Range. As one of the southwest’s most utilized bodies of water, the Colorado River is also one of the most vulnerable to increasing demand and the long-lasting impacts of climate change. Decreasing flows, increased evaporation resulting from higher temperatures, and dwindling snowpack levels continue to increase the gap between supply and demand.

Yampa River

The confluence of the Green and Yampa Rivers

Deerlodge Park:

Flows on July 23, 2018: 98.1 cfs

Average flows on July 23 over the last 33 years: 914 cfs

That’s over 800 cfs less than the past average; that’s roughly 10 percent of the average amount of water.

The Yampa River remains as the last major free-flowing tributary to the Colorado River, the backbone of the West’s water supply. As the Colorado River continues to get exhausted from increasing demand, the Yampa is emerging as a source to meet growing water demands. There have been a number of proposals over the years to dam and divert water from the Yampa to send it to thirsty cities east of the Continental Divide, which would be a disaster for one of the West’s last wild rivers.

Dolores River

Image credit: Gabe Kiritz

Near Bedrock, CO:

Flows on July 23, 2018: 6.04 cfs

Average flows on July 23 over the last 34 years: 93 cfs

That’s less than the past average; that’s roughly 6.5 percent of the average amount of water.

The Dolores River has faced numerous challenges over the years, including dams, high water demands, mining pollution, and climate change. This river is severely threatened, recently scoring a D- on our Colorado Rivers Report Card. However, recent local efforts to revitalize the water have helped build a drumbeat to reinvigorate one of the most unknown and underappreciated rivers in the state.

The steps we take now to protect and improve our rivers will determine the viability — and future — of Colorado’s water. More importantly, what we do now will determine if we have healthy rivers and enough drinking water in the future.