As the climate warms, agriculture in Colorado is on the front lines. The agriculture industry in Colorado is worth $41 billion, and so the impacts that climate change will have on food production should be of tremendous importance to all of us.

We interviewed two researchers to get a sense of what the impacts may be. Colorado State University researchers Dr. Pat Byrne and Dr. Scott Denning both work to understand how crops can adapt to climate change.Their research may help farmers identify ways to adapt to climate change in the future.

The Problems that Colorado Agriculture is Facing

Dr. Denning explained that as the global climate changes, average temperature will rise sharply. Because Colorado is so far inland, this effect will be stronger because large bodies of water help mitigate temperature swings and Colorado is far from our oceans or Great Lakes. We can expect temperature increases in Colorado to be 1.5 to 2 times as large as global averages. Imagine the climate of Albuquerque as far north as Greeley.

Hotter temperatures come with longer growing seasons. But they also bring major problems for agriculture. Hotter temperatures make plants “thirstier” even as soaring temperatures reduce Colorado’s snowpack. That means a hotter Colorado is also a drier Colorado.

So, farmers will be needing to get more water for irrigation. With booming population growth, obtaining water rights is already challenging in Colorado. Dr. Denning’s biggest worry is water issues – for both plants and people. We’ll see an increase in irrigation needs for agriculture as snowpack decreases and city populations increase. As he puts it, “Where the heck are they gonna get the water?”

We get most of our water from snowpack. We divert about 83% of collected water to agriculture. Only 17% goes to cities. We’ve already seen a 20% decrease in snowpack.

Dr. Scott Denning

To make matters worse, climate change also creates more variability. Future summers may be cool and damp one year, but scorching and dry the next. As Dr. Byrne points out, it’s one thing to breed a strain of wheat that can withstand hot and dry. It’s another to create a strain that can withstand all extremes. Farmers will struggle to know what to plant in the face of the extremes predicted. Low yields not only spell economic trouble for farmers, but consumers as well.

The Research

Farmers are already adapting to this unpredictable world. They’re implementing low-till or no-till methods to reduce water loss, getting crop insurance, and starting to plant crops like sorghum and millet farther north. Crop diversity is good insurance against climate variability.

While the farmers who produce our food try to adapt, scientists are also searching for more drastic solutions. Dr. Byrne hopes his research on plant genetics will find or create a strain of wheat that thrives in a wide variety of conditions. He worries that common strains of wheat won’t be profitable for farmers in the future. He says of the struggle, “The biggest challenge is variability, not major changes in one direction. If, for example, we could [selectively breed plants] for increasingly hot and dry places. That would be hard but it would be possible. But what makes it hard is the swinging back and forth.”

Implementation

So far, scientists haven’t come up with a one-size-fits-all climate change solution for agriculture. But they are constantly looking for and researching new ideas. One of these is a technique called precision agriculture. Raj Kholsa, another CSU researcher, lays precision agriculture out like this: “Precision farming can help today’s farmer meet these new challenges by applying the right input, in the right amount, to the right place, at the right time, and in the right manner. The importance and success of precision farming lies in these five R’s.”

So far, scientists haven’t come up with a one-size-fits-all climate change solution for agriculture. But they are constantly looking for and researching new ideas. One of these is a technique called precision agriculture. Raj Kholsa, another CSU researcher, lays precision agriculture out like this: “Precision farming can help today’s farmer meet these new challenges by applying the right input, in the right amount, to the right place, at the right time, and in the right manner. The importance and success of precision farming lies in these five R’s.”

Farmers can remedy financial stress from low yields in other ways as well. Some farmers in Europe have had success in partnering with renewable energy companies to share land. The income from leasing land for windmills or solar can make a difference in tough years. Some farmers may take out crop insurance, which will pay them a sum of money if the harvest is bad.

Acting on climate change is imperative for our future food security as well as the current job security of farmers. Aside from supporting climate change champions politically, you can help by supporting local research institutions as they work to find solutions. Support local farmers financially through CSAs and farmer’s markets, and ask them if they use any of the mitigation efforts mentioned above. Supporting the right people with your dollars can help them make bigger changes in the future.

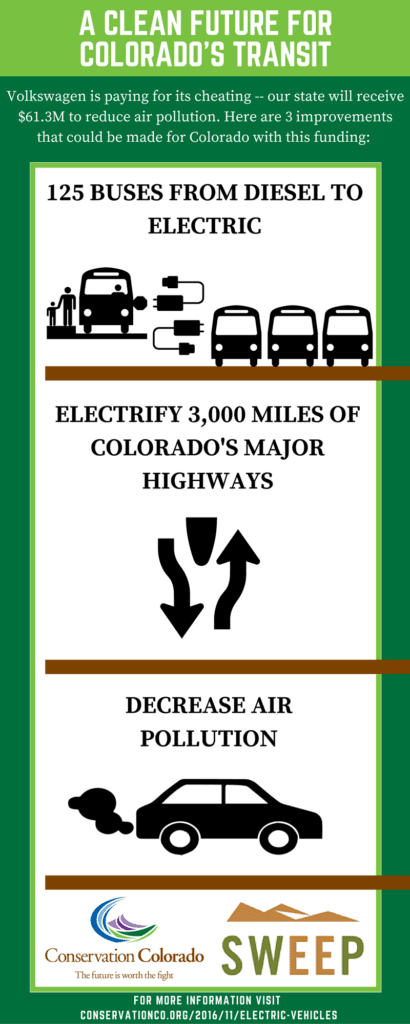

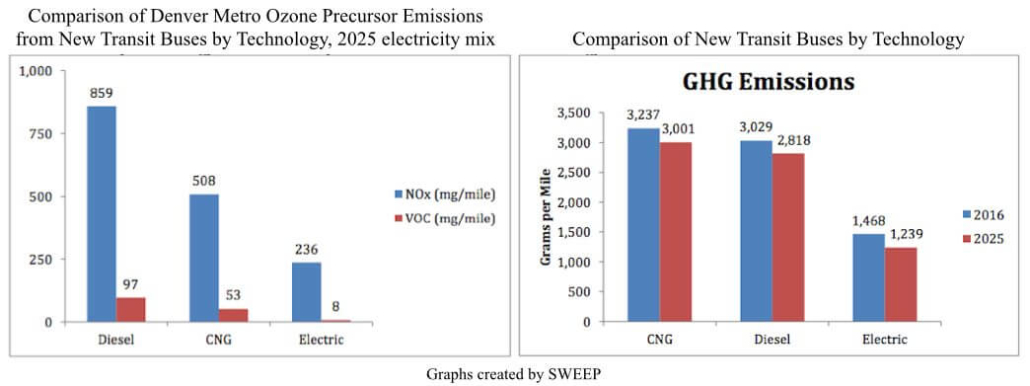

Emissions tests and air pollution limits are in place to protect human health and the air we breathe. Volkswagen’s “too-good-to-be-true” clean diesel cars emitted up to 40 times the legal limit of nitrogen oxides (“NOx”) on the road, but hid these emissions during tests. These smog-forming pollutants, according to

Emissions tests and air pollution limits are in place to protect human health and the air we breathe. Volkswagen’s “too-good-to-be-true” clean diesel cars emitted up to 40 times the legal limit of nitrogen oxides (“NOx”) on the road, but hid these emissions during tests. These smog-forming pollutants, according to

In short, climate change doesn’t just affect high alpine creatures, coastal communities, or big ski resorts. It affects almost all forms of outdoor recreation, threatening our seasons and making planning nearly impossible. Soaring temperatures and unpredictable weather events are a major headache for guides, outdoor enthusiasts, and outing programs.

In short, climate change doesn’t just affect high alpine creatures, coastal communities, or big ski resorts. It affects almost all forms of outdoor recreation, threatening our seasons and making planning nearly impossible. Soaring temperatures and unpredictable weather events are a major headache for guides, outdoor enthusiasts, and outing programs.

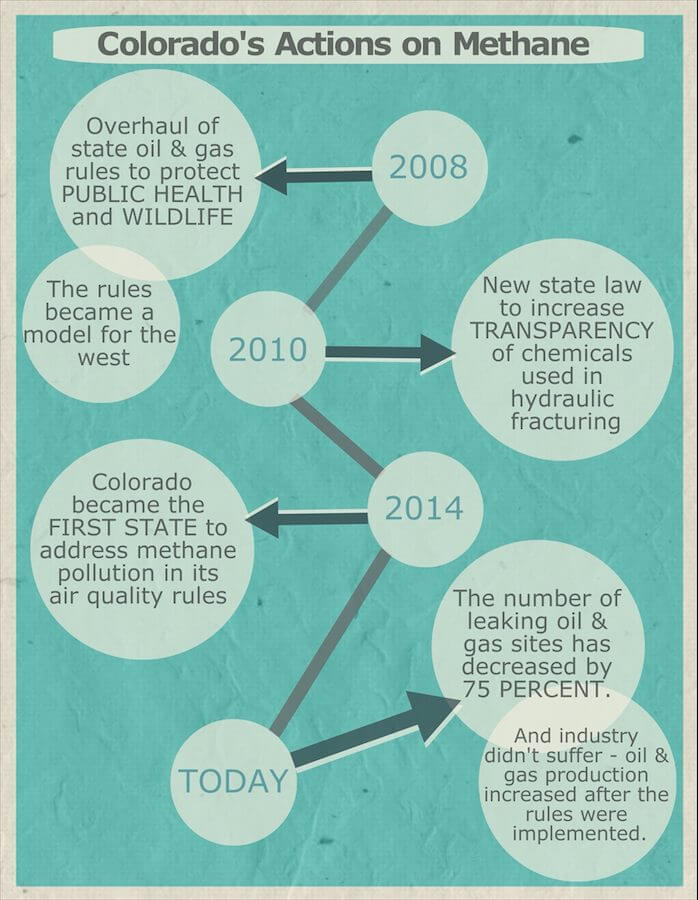

One in three Americans lives in a county with oil and gas operations, and right now, methane is leaking from over a million oil and gas wells. That’s over 7 million metric tons of methane spilling into the air each year – enough gas to heat 5 million American homes (at a cost of over $1 billion in lost methane).

One in three Americans lives in a county with oil and gas operations, and right now, methane is leaking from over a million oil and gas wells. That’s over 7 million metric tons of methane spilling into the air each year – enough gas to heat 5 million American homes (at a cost of over $1 billion in lost methane). What can I use the water for?

What can I use the water for?